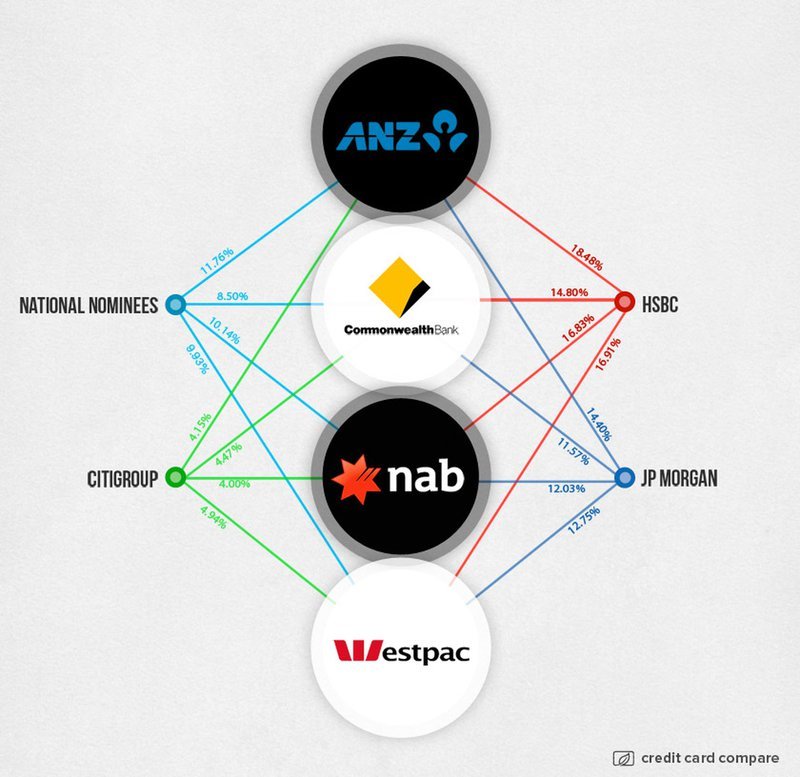

A visualisation of the ownership of Australia's Big Four Banks

Credit Card Compare

In response to concerns over how our financial institutions operate, we commissioned a piece of research on the issue of bank ownership in Australia.

Often consumers who choose to bank with smaller, more independent banks may, in fact, be banking with one of the 'Big Four'. The following examination of who owns the big four (ANZ, Commonwealth Bank, NAB and Westpac) is the logical follow-on from that initial investigation.

Australia’s big four are not merely big, they’re massive. Humongous.

Their combined assets in 2013 stood at $2.86 trillion—or roughly twice the size of Australia’s national income.

They are four of the five largest Australian companies by market capitalisation, together representing more than a quarter of the market. According to a 2012 report by the International Monetary Fund, the big four controlled 88% of residential mortgages and 80% of deposits. By contrast, the biggest six American banks held 30% of total deposits in 2013.

It’s not just banking: the big four own 53% of life insurance premiums, and account for 57.3% of retail investment funds through bank-owned platforms.

It begs the question: if they own so much of Australia’s economy, who owns the big four?

Connections

According to a 2012 report by the International Monetary fund, 'major banks are highly interconnected, as they are among each other’s largest counterparties.’

However, that connection is far from direct. Part of it has to do with banks borrowing from each other, rather than owning large parts of each other.

A study of the Australian bank network by the Reserve Bank of Australia found that more than half of outstanding authorised deposit-taking institutions 'exposure’ in this sense is to the big four.

Because they have so much of the money of the entire system already, when they need to temporarily borrow, there’s few other banks they can go to, so they have to go to each other. That’s a very cosy relationship.

The big four banks vs credit unions

Find out interesting details on the difference between the Big Four Banks vs Credit Unions from our research report.

Custodians

It is in fact the same four names as the top four shareholders in each of the four banks—but it’s not each other.

According to the big four’s annual reports for 2013, here’s who owns ordinary shares:

- HSBC Custody Nominees (Australia) Limited: 16.91% of Westpac; 16.83% of NAB; 18.48% of ANZ; 14.80% of CBA

- JP Morgan Nominees Australia Ltd: 12.75% of Westpac; 12.03% of NAB; 14.40% of ANZ; 11.57% of CBA

- National Nominees Limited: 9.93% of Westpac, 10.14% of NAB; 11.76% of ANZ; 8.5% of CBA

- Citicorp Nominees Pty Limited: 4.94% of Westpac; 4% of NAB; 4.15% of ANZ; 4.47% of CBA

'Custodians’, by definition, hold customers’ securities for safekeeping, in addition to offering other services such as account administration and collection of dividends and interest payments, for a fee.

They are not active participants in decision-making. It would be wrong to imply that by having a 17% stake in Westpac, for example, HSBC also has 17% of the vote: as a custodian, HSBC only processes the proxy votes of the customers for whom it holds the shares—and these customers could be large sovereign wealth funds, or a board member of Westpac, or a family-owned business in Sydney.

Discrepancies in proxy voting do occur, and many uneducated investors aren’t even aware they can cast votes. But in principle, HSBC, in a custodian role, acts only as the messenger, not the decision-maker.

As a wholly owned subsidiary of HSBC Bank Australia Limited, the custody nominees business held more than $700 billion in assets. It is not only in the big four.

The sheer size of its investment capital means that it frequently shows up among the top 5 shareholders for a large number of Australian companies.

In fact, HSBC, JP Morgan, National Nominees and Citicorp all frequently show up together among the top 5 or top 10 shareholders.

They simply represent a very large pile of money, all of which has to be parked somewhere.

HSBC, JP Morgan, National Nominees and Citicorp all frequently show up together among the top 5 or top 10 shareholders in many Australian publicly-traded companies.

Unknown owners?

On a different note, however, that 17% stake HSBC’s custodian arm has in Westpac could, in theory, represent just one person—or four big investors—buying through a variety of mutual funds, each of which has HSBC as their custodian.

It’s a stretch, and it would have to be a very rich group of individuals, but it is possible. Unfortunately, it is practically impossible to track down the identities of those underlying shareholders through the various financial structures that hold shares for each other and on behalf of each other.

Can these hidden shareholders control what Westpac does?

The company points out that as of October 3, 2013, there were no shareholders who had a 'substantial holding’, i.e., in which “they or their associates” have control of 5% or more of the vote.

NAB states the same. Westpac explains that shareholders such as HSBC Custody Nominees (Australia) Limited (16.91% of total shares) 'may hold shares for the benefit of third parties’—the definition of their role as custodians.

Furthermore, Westpac states it is 'not directly or indirectly owned or controlled by any other corporation(s) or by any foreign government.’

But the top 20 registered shareholders held 52.42% of Westpac’s ordinary shares—and that’s a controlling stake. The word 'nominee’ or 'custodian’ pops up in 11 of them.

There’s an independent wealth management group, a closed-end fund, an investment management firm, and so on. Who is behind the actual shares would be, again, practically impossible to determine.

The same names show up among the top 20 for each of the big four banks, with some variation.

The interconnection between the four banks may be even more pervasive, if even less direct. ANZ’s CEO from 2007-2016 was Mr. M R P Smith—who had been with HSBC for most of his 30-year career prior to joining ANZ.

Since 1978, Mr Smith had held 'a wide variety of roles in Commercial, Institutional and Investment Banking, Planning and Strategy, Operations and General Management’, according to ANZ’s annual report, including as director of HSBC Australia Limited from 2004-2007, immediately before he became CEO of ANZ.

In 2008 ANZ also hired its group managing director of human resources and chief risk officer from HSBC, and in 2011 plucked its new global natural resources head from HSBC.

The top 20 registered shareholders hold 52.42% of Westpac’s ordinary shares—and that’s a controlling stake.

Too big to fail?

Whoever it is that owns the big four banks, one thing is clear: if the same four custodian companies own similar chunks of each of the big four, there’s indication that the shareholders behind them do not want one bank to succeed at the expense of another.

The optimal scenario is if all of them win together. And maintain their dominant position, of course.

This post was originally published in May 2014 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy, and comprehensiveness.